Have you ever wondered how many books have been published in Estonian? Are there as few poetry books printed as there are church books? The national bibliography dataset provides an overview of centuries of publishing choices shaped by the spirit of the times. Peeter Tinits, a digital humanities specialist at the Estonian National Library, takes a look at the dataset and provides an overview of the most important trends.

As a result of generations of collecting, the Estonian National Bibliography has been compiled – a list that includes all printed works related to the Estonian territories or published in the Estonian language, containing data from maps to Bible translations. The first such list was completed in the 1830s, nearly 200 years ago.

Johann Heinrich Rosenplänter, who gathered around him a group of enthusiasts of the Estonian language and culture, wrote and published the journal Beiträge zur genauern Kenntniss der ehstnischen Sprache ("Contributions to a More Accurate Knowledge of the Estonian Language") for nearly 20 years, from 1813 to 1832. In 1832, he also published an overview of the works that had been released up to that point. In this work, he presented a list of 384 Estonian-language printed books, categorized by subject. The literati also included information about several manuscripts that had not yet been printed, as well as books in other languages that dealt with the Estonian language or Estonian-speaking regions.

Rosenplänter's works have been digitized and are available for reading in the digital archive of the University of Tartu. His manuscript list is even longer and has been preserved to this day in the archive of the Estonian Literary Museum.

Through several steps, Rosenplänter's list became the foundation for a larger project, „Bibliotheca Estonica“. This led to the publication of „Eesti kirjanduse lühikene ajalugu“ ("A Brief History of Estonian Literature") in 1844 by the scientific society Õpetatud Eesti Selts, and later to the ten-volume „Eesti Rahva Muuseumi Arhiivraamatukogu 1632.–1917. aastal ilmunud eestikeelsete raamatute nimestik“ ("Catalogue of Estonian-Language Books Published in 1632–1917 in the Archive Library of the Estonian National Museum") in 1932. During the Soviet period, it was published as „Raamatukroonika“ ("Book Chronicle") from 1940 to 1991, and since 1993, it has been known as „Eesti retrospektiivne rahvusbibliograafia“ ("Estonian Retrospective National Bibliography"). Since 2004, this has been gradually digitized.

The National Bibliography consolidates information in the spirit of Rosenplänter about all works that have been published in any language within the present-day territory of Estonia, as well as works published outside of Estonia that are either in Estonian or address topics related to Estonia or Estonians. It is currently available as open data through the Digilab of the National Library.

By looking into the data, it is possible to find an answer to the posed question. As of early November this year, 218,856 books had been published in Estonian, and 87,521 books related to Estonians and Estonian territories had been published in other languages. Naturally, it would be unrealistic to expect to know every book from the nearly 600-year history of printing in Europe. However, the compilers of the bibliography assess its representativeness as quite good, estimating that it covers 95–99 percent of all prints.

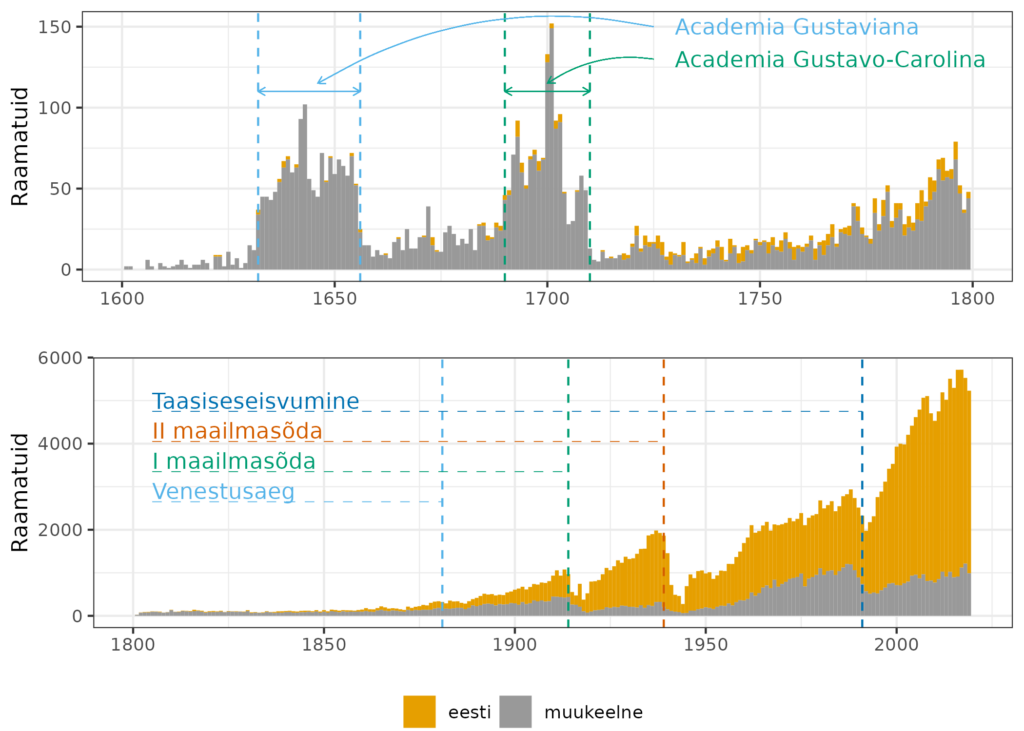

The data can also be explored over time. In Figure 2, it is immediately noticeable how the Estonian-language literary space emerged alongside other languages. Between 1600 and 1800, Estonian-language works were still a rarity, but in the 1850s, they began to experience a rise in popularity. Soon, these works made up the majority of the content in the dataset.

Historical events of interest are also evident—book printing in the 17th century peaked during the periods when the University of Tartu was active. Understandable declines can be observed during the Estonian War of Independence and World War II. Looking at the last 150 years as a whole, the growth trend has been relatively stable.

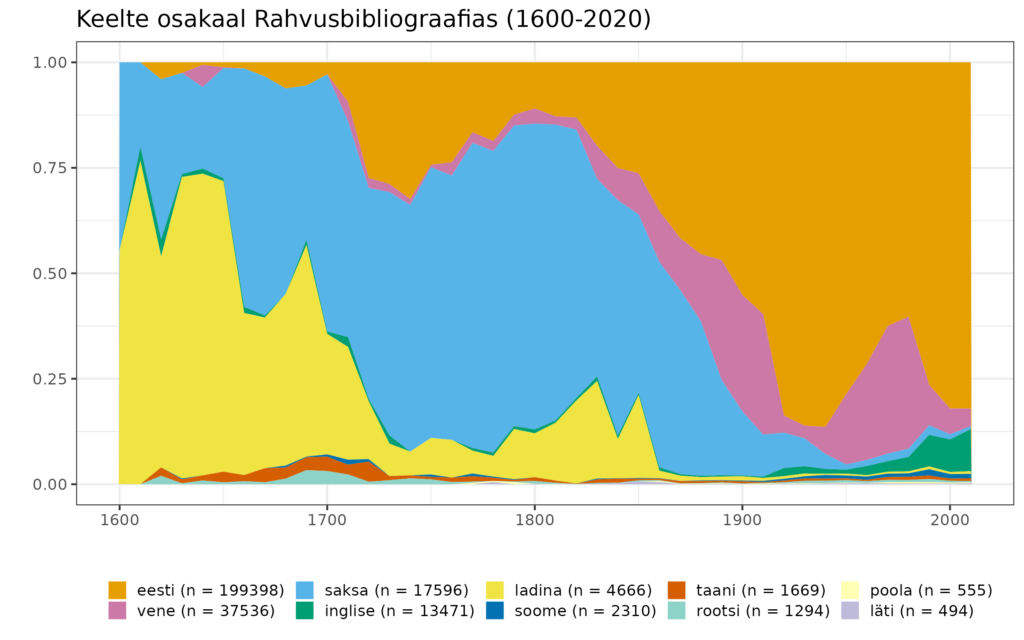

It is also possible to examine the languages in which other works have been published. To do this, the information about languages in the bibliography itself needs to be enhanced by running a language detection algorithm on the titles of the works1. As a result, language information is available for 99 percent of the works.

An examination of the data uncovers historical trends. The Russification era increased the proportion of Russian-language publications from the 1880s until World War I, primarily at the expense of German. Meanwhile, the share of Estonian-language publications continued to grow steadily during the same period.

During the era of independent Republic of Estonia, other languages decreased to just 15 percent of publications, reaching a similar balance again in the 1990s. However, by then, English had replaced German as the dominant secondary language. During the Soviet era, the number of Russian-language publications gradually increased, but their share never exceeded 30 percent of the total. Notably, a significant portion of Estonian-language literature from this period came from the Estonian diaspora and was often not accessible within Estonia.

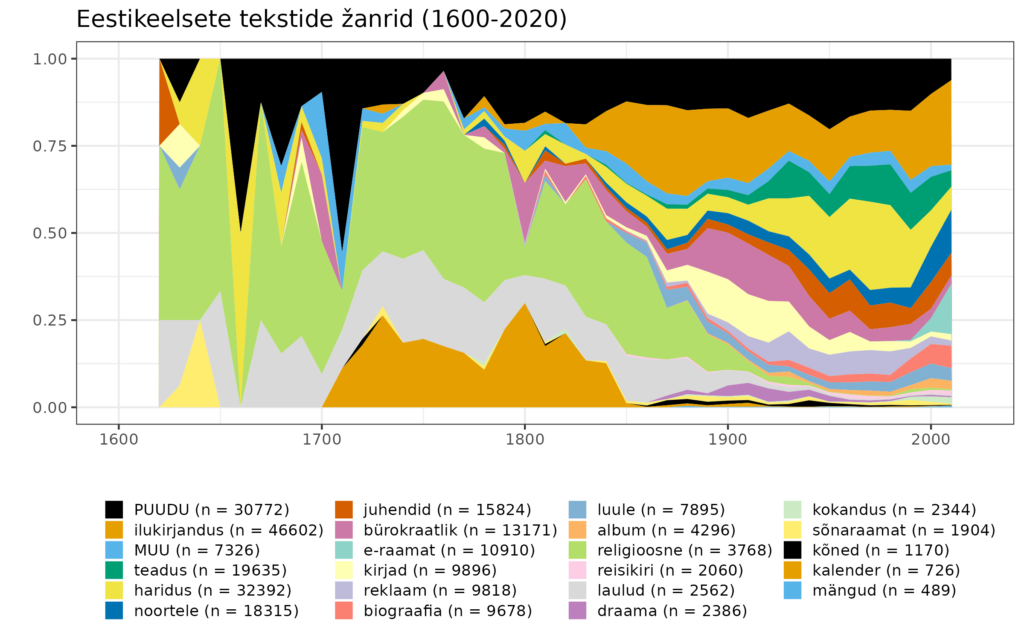

In addition to language, the dataset contains information about the content of the works. Figure 4 provides a genre composition of Estonian-language works published between 1600 and 2020 (the bibliographic genre categories have been slightly simplified and standardized for clarity). The figure highlights the increasing individualization of Estonian reading experiences. In the 18th century, central genres were religious texts, hymnals, and almanacs, meaning that people tended to read relatively similar works.

Although the literacy rate in Estonian territories was exceptionally high under Scandinavian influence—reaching 60–80 percent around 1800 and approximately 95 percent by 1900—it is likely that for many, this literacy was limited to the need to learn to read in preparation for confirmation and marriage. In daily life, however, only a small portion of the population engaged in regular reading at first.

Throughout the 19th century, the range of reading materials diversified, allowing readers to follow their personal journey. Genres emerged that were linked to individual experiences of understanding and creating texts—such as fiction, school textbooks, and even society constitutions. Over the century, hymnals and almanacs, which had previously held great significance, gradually disappeared. For these, it was enough if someone in the family or social circle maintained an interest in reading, as the important content could be passed on through oral storytelling.

The information presented in the figure is likely not a great surprise to a history-minded reader. What may be more interesting is how, based on the book registry, it is possible to gain a relatively broad, bird's-eye view of Estonian history in a more general sense — how people lived and what they wrote about — simply through the use of metadata.

The dataset itself, however, opens up opportunities for many more precise studies. For example, it allows for an analysis of how the book market was divided among different publishers in 1920, how the typical career of an author looked at the end of the 19th century, or which translations made their way into Estonian in the early 1990s.

While these studies can already be conducted using the current National Bibliography, the future may offer opportunities for even more complex analyses. A similar national bibliography exists for most European countries, and several research groups are working to consolidate and standardize this information. Once the databases are interconnected, it would be possible to study, for example, the history of printed works around the Baltic Sea in the 18th century and map the similarities and differences in the spread of contemporary ideas.

An additional opportunity arises from combining datasets with full texts. According to the National Bibliography data, a third of these books have already been digitized, and this proportion is steadily increasing. By placing the content of digitized texts within the context of the bibliography, we can better assess what topics were written about or create focused text collections—whether for linguistic research or for works of art created by artificial intelligence.

1. Google's Compact Language Detector 2 (R packet cld2) and a word-cluster-based text categorizer textcat (R packet textcat) was used.

The research code and data are accessible here: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/9DX3G

This post has been translated using ChatGPT.

National Library of Estonia

Tõnismägi 2, 10122 Tallinn

+372 630 7100

info@rara.ee

rara.ee/en