Would you like to see how big data tells history? Come and explore with the Digilab's tool what has been said about cars in Estonian newspapers throughout history! First read the blog post and then try the tool here.

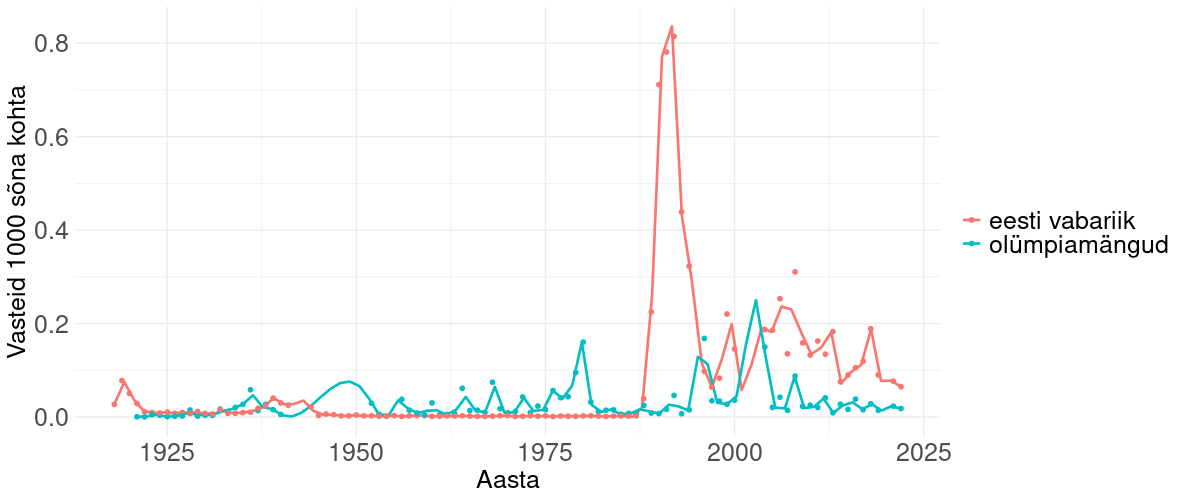

To conduct the analysis, we use a word cluster counter developed in Digilab, which allows us to analyze the frequency of words and word combinations over time. For this purpose, word clusters appearing in digitized Estonian newspapers have been reviewed. These one-, two-, or multi-word phrases can provide insights into topics that were prevalent in print at different times. For example, it is not surprising that the phrase "Eesti Vabariik" (Republic of Estonia) peaks around 1991, or that "olümpiamängud" (Olympic Games) increases in frequency roughly every four years (see Figure 1 below).

The word cluster counter currently draws on 54 newspapers, covering the period from 1857 to 2023. This includes major well-known Estonian publications such as Postimees, Eesti Päevaleht, and Sakala, older papers like Perno Postimees and Eesti Postimees, as well as local papers like Võrumaa Teataja and Muhulane. The counter does not display the absolute frequency of words and phrases but instead indicates how many times a given word appears per 1,000 words each year. This approach is used for two reasons: first, the total volume of journalism has grown immensely over nearly two centuries; second, not all newspapers are digitized or simultaneously available, meaning the amount of text varies by year. It is important to note that the trends shown by the tool should not be interpreted literally, as the digitization process is not flawless. Additionally, one must keep in mind that word frequency in journalism primarily reflects what the media focused on at any given time.

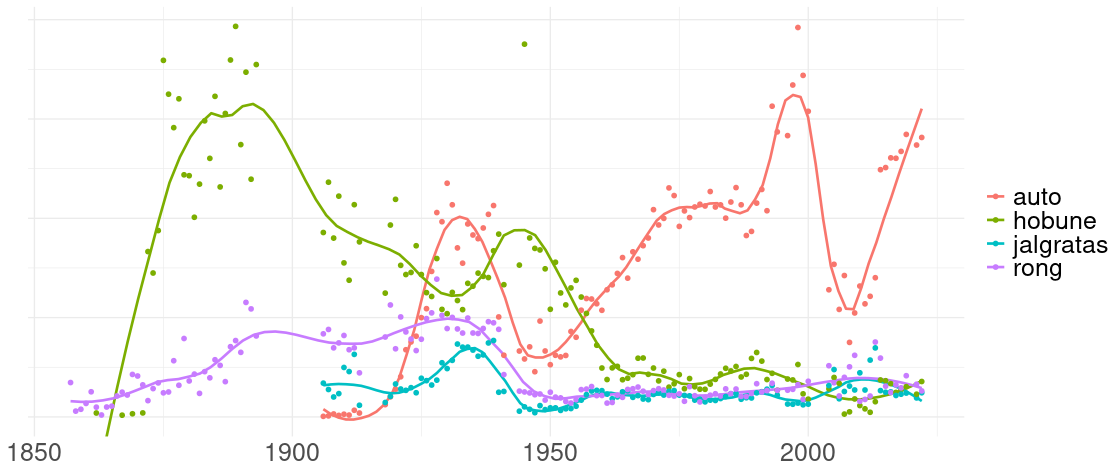

With this in mind, let us first examine how the frequency of the word auto (car)changes over time and compare it with some other common modes of transportation. Figure 2 compares the search terms auto (car), hobune (horse), jalgratas (bicycle), and rong (train). As shown, until the mid-20th century, hobune appears most frequently, although rong is also quite common. This pattern generally reflects the infrastructure of the time: the most prevalent means of transportation and power source was the horse, essential for every household. Trains, which arrived in Estonia in the 1870s and whose benefits were heralded by J. V. Jannsen in the first issue of his newspaper1, became symbols of industrial society and modernity. The bicycle, which began to spread rapidly in the late 19th century, was initially also seen as an avant-garde and modern mode of transport2.

As the graph shows, the word auto first appears in the data around 1910. Interestingly, this was not due to the replacement of an earlier term—automobiil (automobile) appears at the same time but fades away shortly thereafter3. From that point, it takes only twenty years for auto to become the most mentioned mode of transport in journalism, surpassing even hobune (horse). This aligns well with the recollections of people who lived during that time, noting that cars became a common sight on the streets by the mid-1930s4.

In Soviet-era newspapers, we can simultaneously observe a rise in the frequency of the word auto and a decline in mentions of other modes of transport. Notably, auto peaks in the early 1970s, reflecting the explosive growth in private vehicle ownership during this period. It was in the 1970s that cars became primarily privately owned and associated with family or personal use, in contrast to vehicles belonging to collective farms or workplaces. As cars became a regular part of everyday life and the trend of automobilization continued during the re-independent Republic of Estonia, mentions of auto in the press also increased.

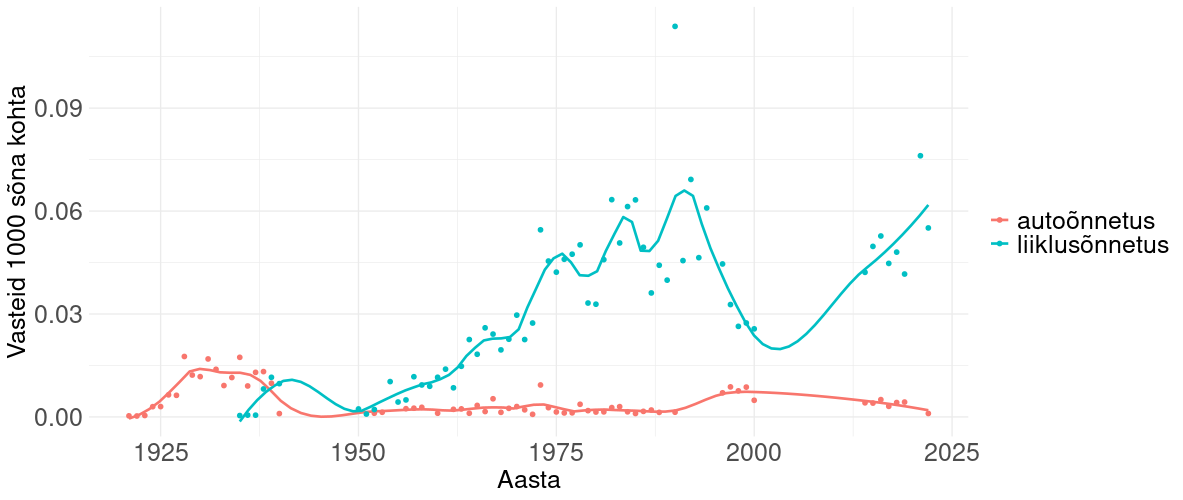

The spread of cars is also reflected in the emergence of various car-related terms. For instance, traffic accidents, which are inherently newsworthy events, frequently appear in the dataset. In the 1920s and 1930s, the term most commonly used was autoõnnetus (car accident). However, by the mid-20th century, the preferred term shifted to liiklusõnnetus (traffic accident), as shown in Figure 3.

It can be assumed that over time it became self-evident that any traffic accident involved at least one motor vehicle, most likely a car, and therefore it became unnecessary to specifically mention this in the terminology. In general, the word liiklus (traffic) began to appear in use in the mid-20th century and has become increasingly common since then.

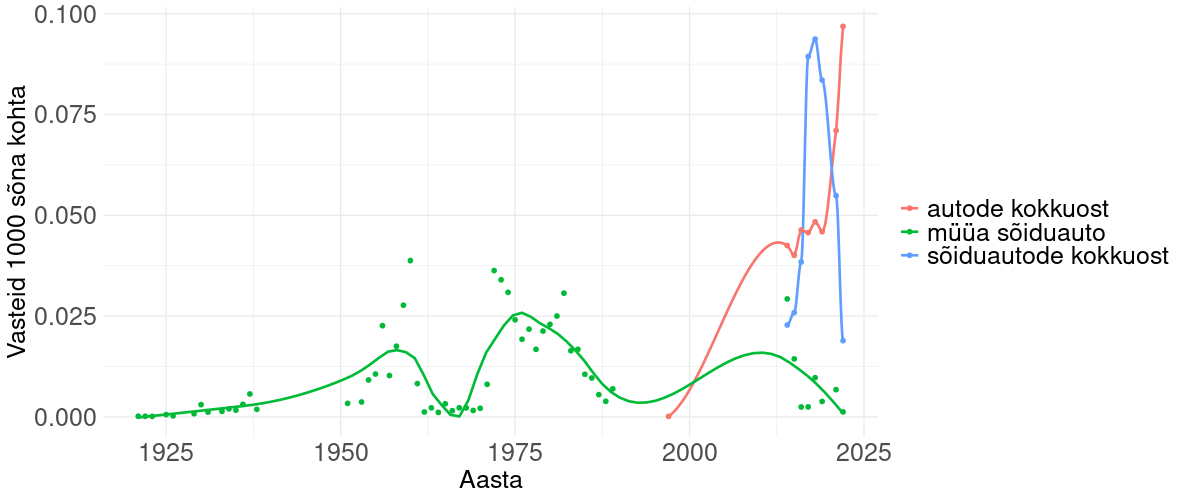

Since the tool allows us to examine the frequency of word clusters, we can also explore the occurrence of different word pairs (and triplets) over time. Figure 4 shows the frequency of three phrases: müüa sõiduauto (selling a car), autode kokkuost (car buying), and sõiduautode kokkuost (buying cars).

The relatively high frequency of the phrase müüa sõiduauto (selling a car) between the 1950s and 1980s can be attributed to newspaper advertisements where people sold their used vehicles. Buying a car was notoriously difficult during the Soviet era, as one first had to obtain a purchase permit, which could take years to secure. At the same time, a lively used car market existed, and prices for second-hand cars were often higher than for new ones, as the former were driven by demand, while the latter had artificially fixed prices set by the state. Sometimes, people managed to acquire more than one car by scheming with purchase permits (even though only one car was allowed per family), and in such cases, they could sell the old car at a profit5.

Miks aga puudusid nõukogudeaegsetes lehtedes igasugused ostu- ja kokkuostukuulutused? Põhjus on lihtne – defitsiitse kauba ostukuulutus ei omanud mingit mõtet ning selle ülespanija oleks lihtsalt välja naerdud („Ja mis siis, et sa autot tahad osta? Kes ei tahaks!“). Nii mõnedki teavad lugusid rääkida sellest, kuidas nõukogude ajal võis automüügikuulutuse peale kohale ilmuda kolmekordne arv soovijaid, sularaha kotis.

The reason why there were no purchase or buy-back advertisements in Soviet-era newspapers is simple – an advertisement for purchasing scarce goods made no sense, and the person posting it would simply be mocked ("So what if you want to buy a car? Who wouldn't want one!"). Many people recall stories of how, during the Soviet era, a car sales ad could attract three times as many buyers, all with cash in hand.

As we can see, this is not the first time that cars have attracted so much public attention. The analysis of historical big data allows us to explore how the development of transportation has been reflected in the media over the past 170 years, and how it has been influenced by the economic context and political situation.

Did you have any thoughts while reading about which words and phrases' frequencies could be further explored? Feel free to give it a try and experiment with the Digilab's word cluster counter here! Feel free to contact us on digilab@rara.ee.

1. Perno Postimees ehk Näddalileht, nr. 1, 5th of June 1857, pp. 3-4.

2. Muide, Tambet (2023). Eesti XIX ja XX sajandi jalgrattakultuur. Sirp 9th of June 2023. https://www.sirp.ee/s1-artiklid/arhitektuur/eesti-xix-ja-xx-sajandi-jalgrattakultuur/

3. In fact, the words auto and automobiil were already used in newspaper columns earlier, but they appeared so rarely that the word cluster counter does not show them.

4. Rattus, Kristel (2013). Nõukogude ajal algas autode ajastu: autokasutuskogemusest Nõukogude Eestis Eesti Rahva Muuseumi küsitluslehtede vastuste põhjal. Runnel, Pille; Kaalep, Tuuli; Ruusmann, Reet; Sikka, Toivo (Toim.). Eesti Rahva Muuseumi aastaraamat 56. (14−43). Tartu: Eesti Rahva Muuseum, lk 21.

5. Rattus (2013), lk 28.

6. ERR. Eestis seisab kasutuseta pea iga kolmas sõiduk. 10th of August 2023. https://www.err.ee/1609058309/eestis-seisab-kasutuseta-pea-iga-kolmas-soiduk

7. ERR. Vanametalli kokkuostu jõuavad viimasedki nõukogudeaegsed autoromud. 8th of April 2022. https://www.err.ee/1608558889/vanametalli-kokkuostu-jouavad-viimasedki-noukogudeaegsed-autoromud

This post has been translated using ChatGPT.

National Library of Estonia

Tõnismägi 2, 10122 Tallinn

+372 630 7100

info@rara.ee

rara.ee/en