Estonian National Bibliography, which compiles data on book publishing, conceals hundreds of other names — individuals who either upheld or accelerated the events of the Estonian National Awakening.

Data scientist Krister Kruusmaa from the National Library of Estonia delved into the extensive publishing database in the Digilab and unearthed fascinating new discoveries and connections among writers, printers, and booksellers.

By exploring the extensive Estonian National Bibliography1, we can shift the focus from the books themselves to the people behind them. Since the bibliography not only records authors but also other contributors like publishers, translators, and illustrators listed on printed works, it offers rich opportunities to study Estonian literary figures and their interconnections in the history of publishing.

To derive new insights, network analysis is employed, enabling a mathematical approach to the data and the visualization of results. This method has gained traction across numerous disciplines, experiencing a surge in popularity with the study of social media. However, network analysis has also been used to investigate, for example, the correspondence of Tudor-era English elites, the spread of news, the formation of political factions, and more. In Estonia, the method was recently successfully applied to analyze 19th-century parish court records2.

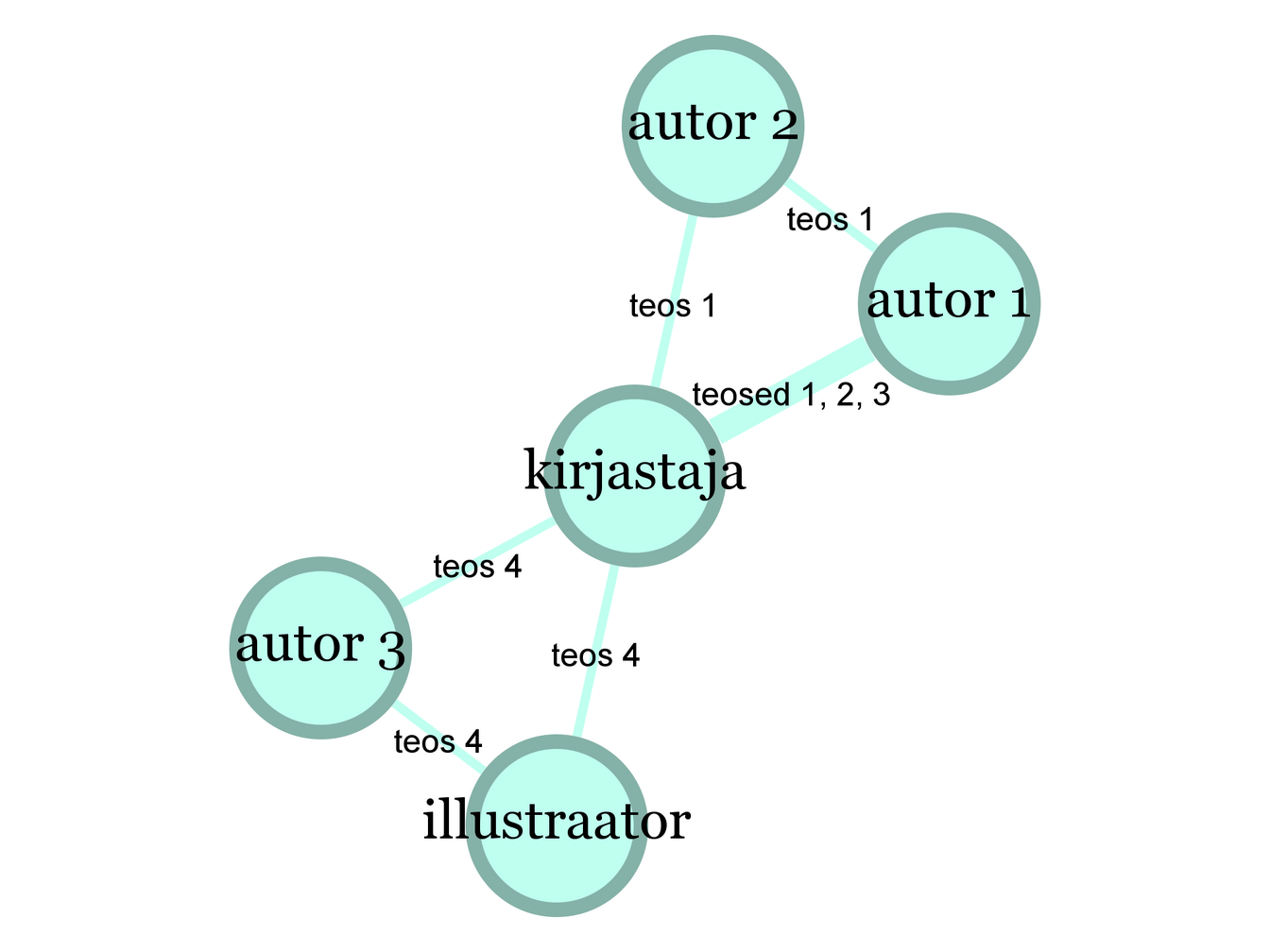

To construct any network, its elements—nodes (or vertices) and the edges (or links) between them—must first be defined. In the network derived from the National Bibliography, each node represents a specific historical individual. A connection between two nodes is formed when both individuals are listed on the same printed work—for instance, one as the author and the other as the publisher, or both as co-authors.

A single work can generate multiple edges when it involves several contributors, such as an editor, translator, and preface author (see an example in Figure 1). Network constructed this way links individuals and groups of people who collaborated on publishing a particular work. Attributes such as years of activity, primary roles, or preferred languages can be added to the nodes and edges, uncovering relationships that might otherwise remain hidden using traditional methods.

Overview of the Analysis

A network based on the entire dataset of the National Bibliography would be vast, comprising approximately 20,000 nodes and 90,000 edges, as roughly 300,000 books have been published over time. To make the analysis more manageable, we focus on a specific period: Estonia's National Awakening, defined roughly as 1855–1885. This timeframe spans from the founding of newspaper Perno Postimees and the publication of Estonian national epic Kalevipoeg to Jakob Hurt's departure and Carl Robert Jakobson's death. It includes key milestones such as the publication of Kalevipoeg, the first nationwide song festival, and the establishment of various newspapers and societies.

To create a cleaner network, we exclude individuals with incomplete information, such as those lacking recorded years of activity. We further narrow the focus by removing figures not active during this period, such as Martin Luther, whose works continued to be published but who lived centuries earlier. Additionally, we omit minor contributors with only one or two publications and that publisher was missing.

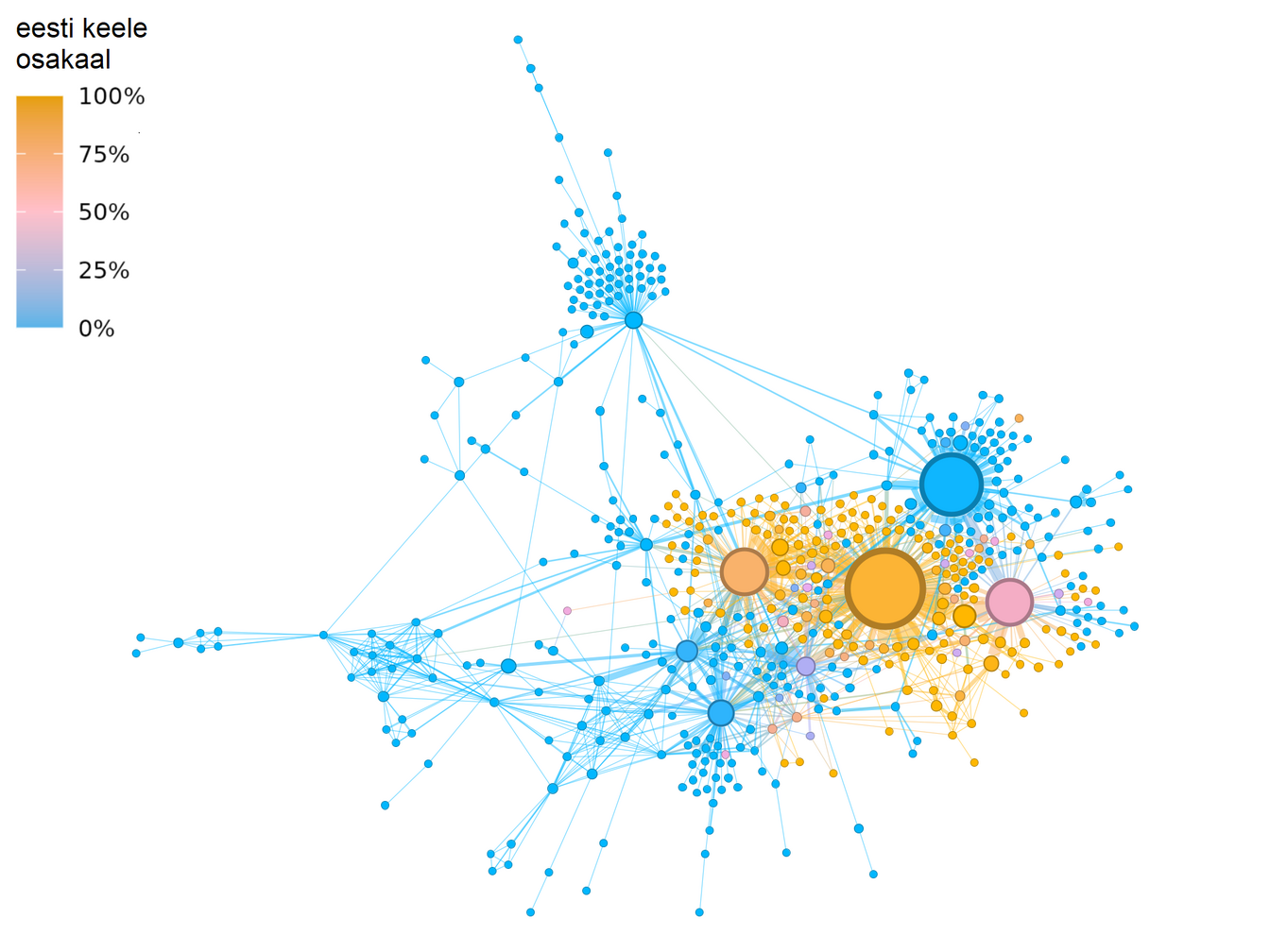

The resulting network consists of 518 nodes and 1,107 edges.3 We designed the graph so that the size of each node corresponds to the number of publications by the individual, while the color indicates their use of the Estonian language. In Figure 2, the literary and publishing landscape of the Estonian National Awakening as reflected in the bibliography is depicted. The network includes 287 individuals who primarily published in German, 173 in Estonian, 43 in Russian, and 15 who predominantly used other languages.

The data reveal that during the period 1855–1885, Estonian was still a minority literary language, as reflected by the smaller number of orange nodes (representing Estonian-language authors) in the network. However, these Estonian-language authors are not isolated; instead, they form an integral structural component of the network, interconnected with non-Estonian-language nodes.

This is significant. Estonian-language publishing emerged organically from the previously dominant German-language literary tradition. On the network level, this means that Estonian-language authors frequently had ties with German-language authors. They also collaborated with the same publishers, illustrators, and other contributors.

Kreutzwald’s Network

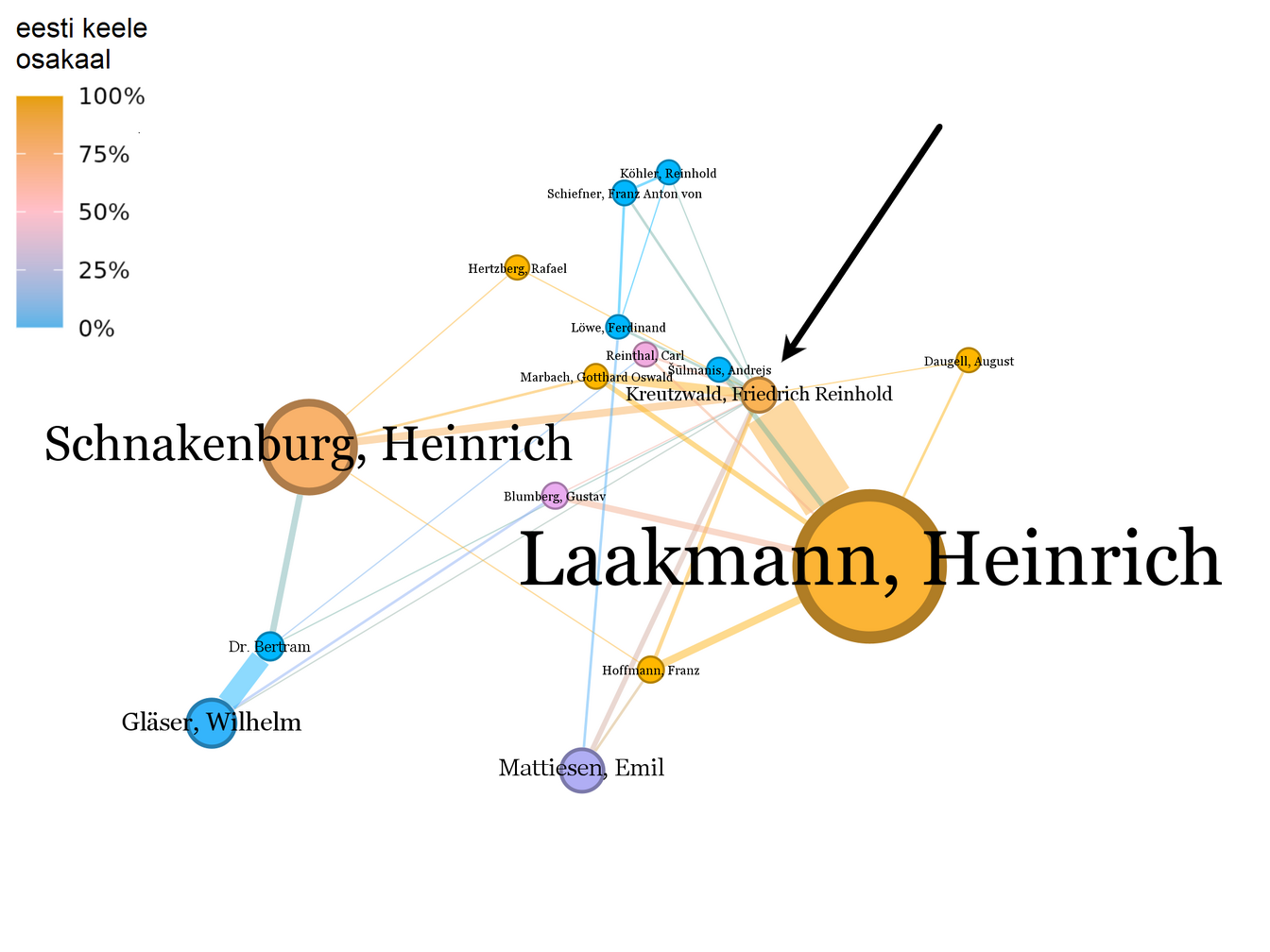

To illustrate this, let’s examine Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald’s position within the network. By isolating Kreutzwald’s node along with all its directly connected nodes, we can better understand his role (see Figure 3).

Kreutzwald’s personal network is roughly evenly split between Estonian-language and other-language nodes. His connections include Baltic German estophiles, members of the scientific society Õpetatud Eesti Selts, and collaborators abroad who helped publish German translations of Estonian folk tales in Halle and Saint Petersburg.

Among the largest nodes in Kreutzwald’s network are those of publishers Laakmann and Schnakenburg, whose roles will be explored in greater detail later. Given the diversity of Kreutzwald’s collaborators and their communities, it’s reasonable to assume that his connections to various individuals and groups made him a central figure in the publishing network of his time.

Measuring Centrality in the Network

The network is more than a visualization; it is a mathematical construct that can be analyzed using specific formulas and algorithms. One such option is the calculation of node centrality. There are several ways to approach this, but in the context of this analysis, we focus on betweenness centrality. It means how often a particular node lies on the paths between all other nodes.

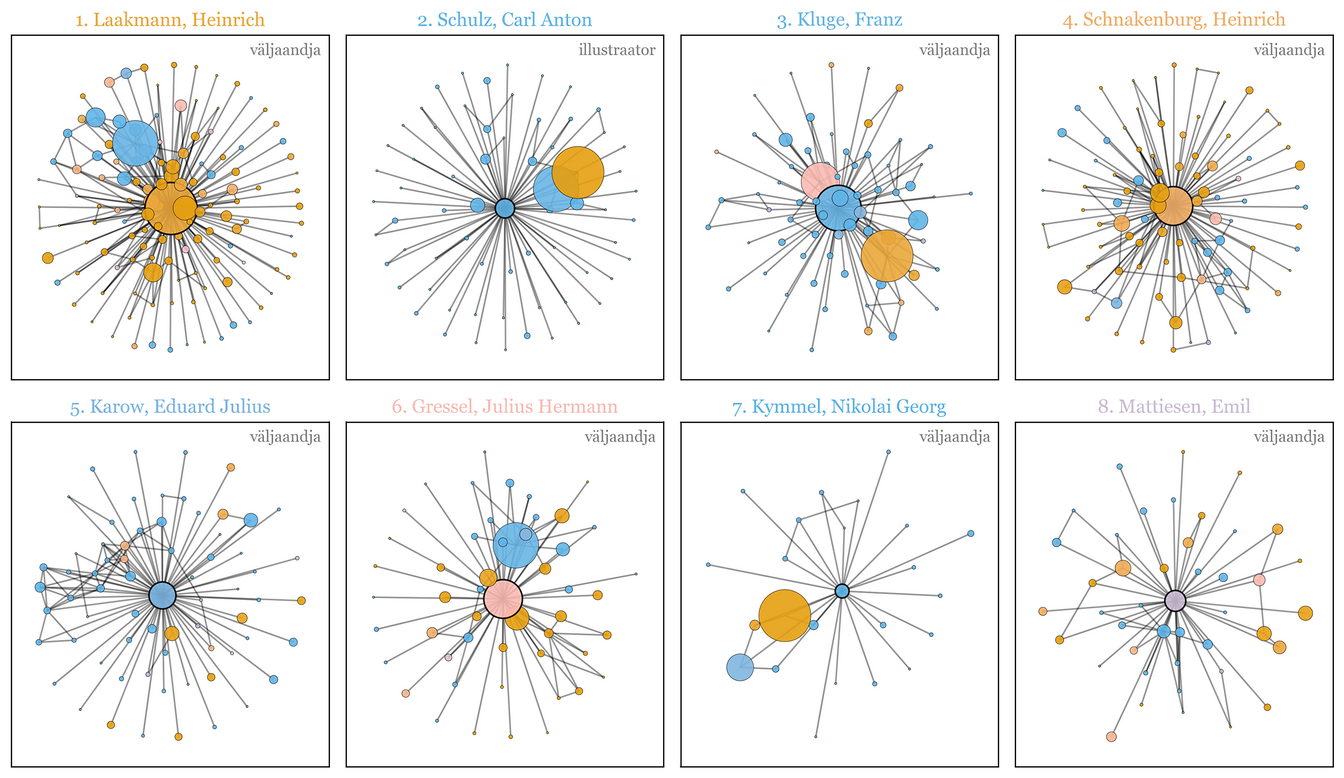

Nodes with high centrality are those that act as key bridges, connecting many other nodes or clusters within the network. In Figure 4, the eight most central figures from the 1855–1885 period are depicted along with their personal networks—that is, the nodes they were directly connected to.

The most central nodes are those that connect a large number of other nodes or groups of nodes. Figure 4 shows the eight most central figures during the period 1855–1885, along with their personal networks, i.e., the nodes they were directly connected to.

Kreutzwald does not appear among the most central figures in the ranking; he is placed only 23rd. It is immediately noticeable that the central figures in the network are not authors but rather publishers and designers. This is logical for several reasons: publishers connect with everyone whose works they publish, while authors typically work with only one or two publishers. Similarly, prolific designers often collaborate with many authors. The most central figure in the network, Carl Anton Schulz, was the owner and director of a photography studio and lithography workshop in Tartu.

New Figures in the Awakening Era

Among publishers, the most central figure in the entire network is Heinrich Laakmann, a publisher in Tartu who printed many of the most important texts of the National Awakening. A member of the scientific society Õpetatud Eesti Selts, he also ran the first bookstore specializing in Estonian-language books. Heinrich Schnakenburg primarily published Estonian-language books as well. Julius Gressel, based in Tallinn, split his output roughly equally between Estonian and other languages, as shown by the pink color of his node.

The Schnakenburg family only began publishing in the latter half of the 1870s, while Laakmann and Gressel were already printing a significant amount of Estonian material in the 1840s. Interestingly, these two were not local to the region—they were Germans from Germany. For instance, Gressel inherited his printing business from his immigrant father. One might ask whether their outsider status freed them from local prejudices and allowed them to identify the emerging market niche of Estonian readers.

All other printers visible in Figure 4 were Baltic Germans, except for Karow, another immigrant who worked as the University of Tartu’s publisher. His role excluded Estonian as a primary language of his output.

The Most Central Disseminator of Estonian Writing Culture

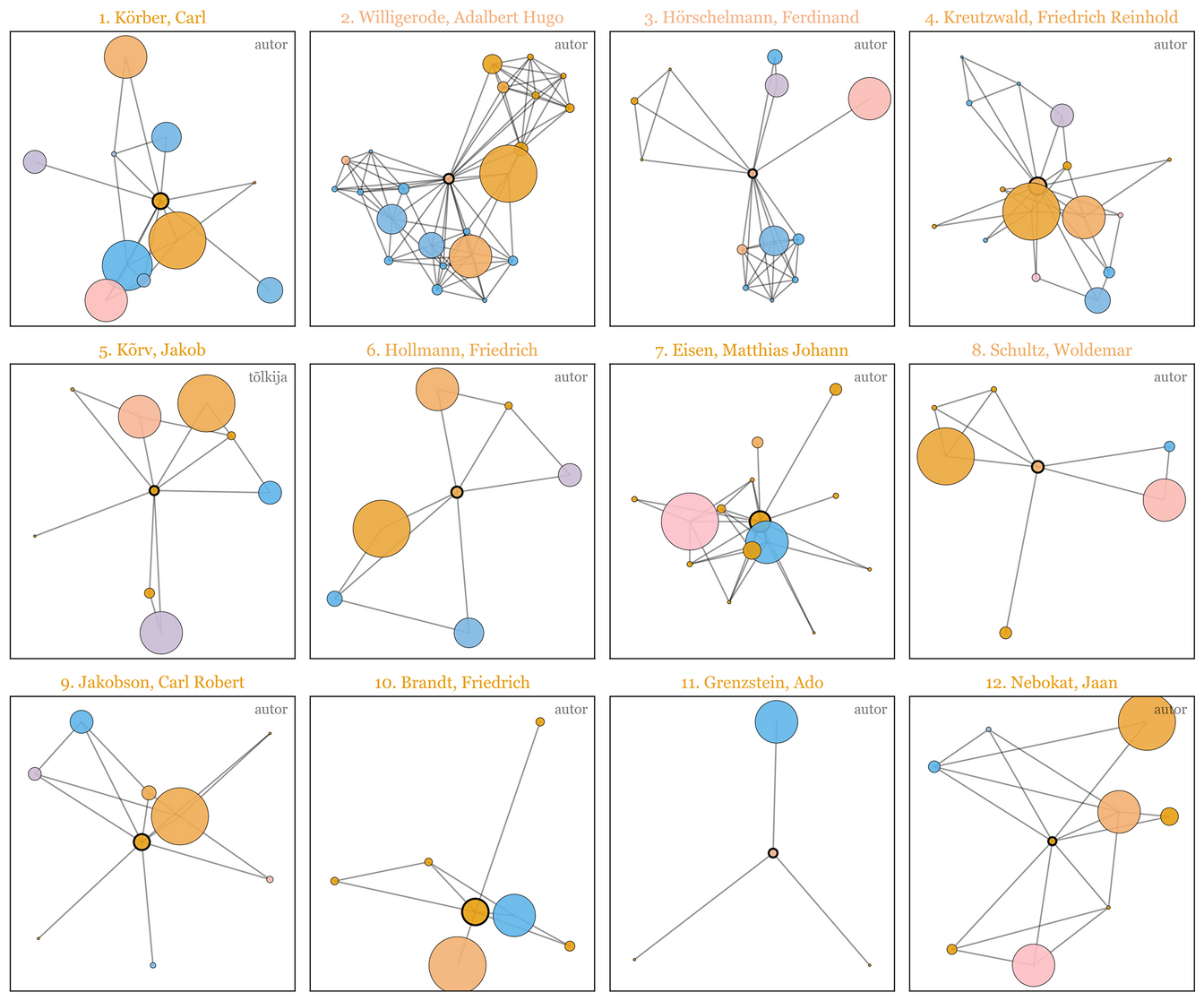

Returning to centrality, let us focus only on those who primarily published in Estonian and exclude publishers. Figure 5 presents the 12 most central disseminators of Estonian-language literature. Alongside Kreutzwald, the list includes several well-known cultural figures such as Carl Robert Jakobson (writer, politician and teacher) and Matthias Johann Eisen (folklorist). However, it also features lesser-known individuals.

The most central figures are, in fact, Baltic German literati: C. Körber, A. H. Willigerode, and F. Hörschelmann. These, along with F. Hollmann (ranked 6th) and W. Schultz (ranked 8th), were Baltic German clergymen who published Estonian religious and educational texts. Willigerode also chaired the committee for the first Estonian Song Festival, while Hollmann led a seminary for village schoolteacher training.

Others in the top 12 include Jakob Kõrv and Ado Grenzstein, as well as schoolteachers Friedrich Brandt and Jaan Nebokat. Kõrv and Grenzstein were active in journalism, editing the publications Valgus and Olevik, respectively. Network analysis highlights Kõrv's significant role as a literary translator, having translated works by Pushkin, Gogol, and Dickens into Estonian. However, both Kõrv and Grenzstein later became critics of the Estonian national movement and supporters of Russification policies.

Network analysis uncovers new connections and highlights lesser-known but significant figures in Estonian cultural history. When discussing the Awakening era, most people might not realize the crucial role that printers and booksellers played in developing Estonian-language literature. It may also surprise some that many of the era's most central Estonian-language authors were Baltic Germans or relatively forgotten figures, while Lydia Koidula, for instance, ranks only 39th in centrality.

Koidula’s Influence Across Periods

Several factors explain Koidula's modest position in the network of the National Awakening. Firstly, the analysis relies on bibliographic data focusing on books, excluding key sources such as journalism, private correspondence, or social activities. These elements were significant in Koidula's contributions but are outside the scope of this particular network.

Secondly, her posthumous fame likely exceeds her contemporary influence, as her role as a symbol of the National Awakening was solidified only later. Koidula became an emblematic figure due to the enduring appeal of her poetry, which transcended the immediate context of her era. Finally, let's try to test this hypothesis using network analysis.

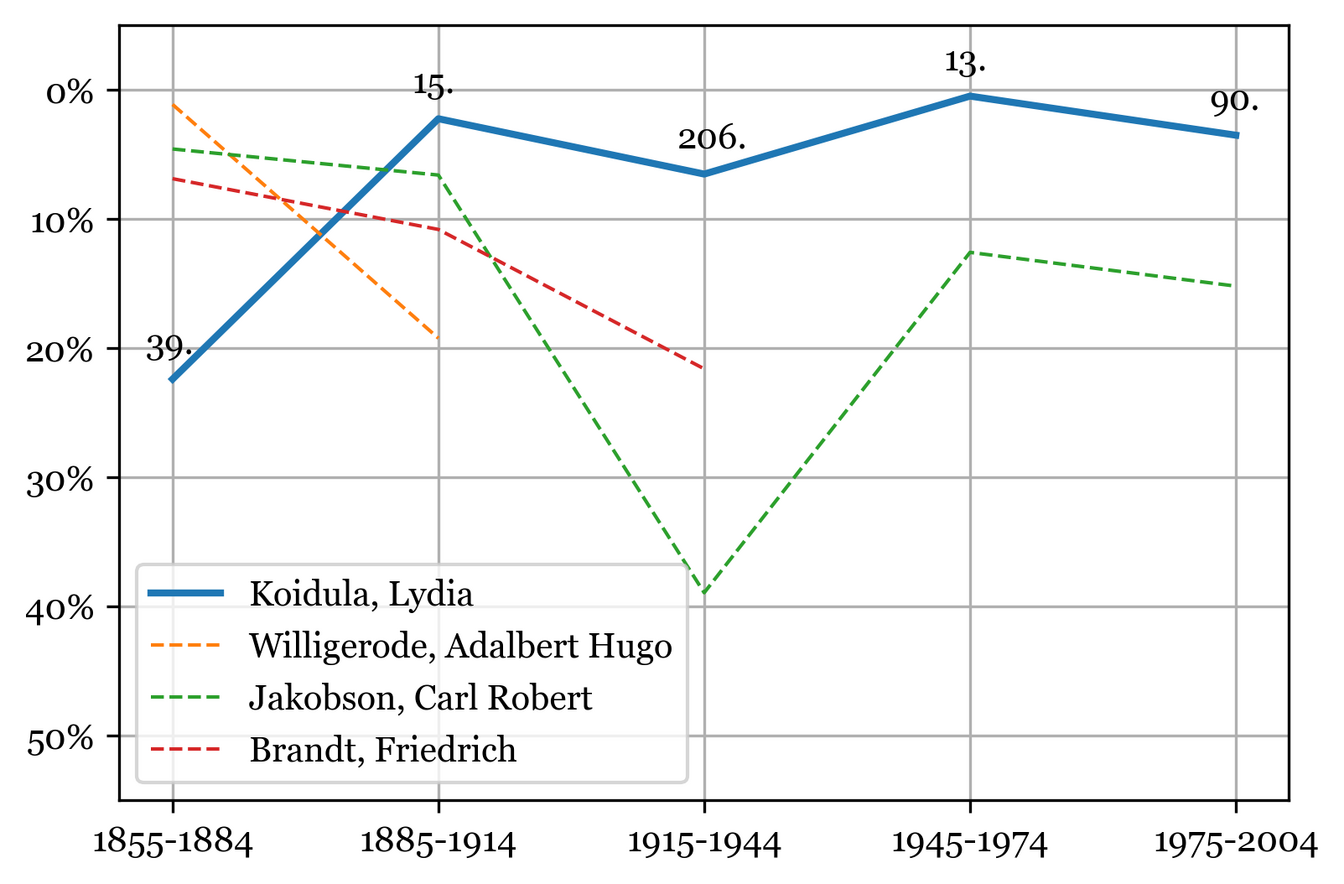

So far, we have examined the period 1855–1885 and books related only to individuals living during that time. However, to study Koidula's significance in later periods, new networks must be created that also take into account the works of deceased authors.

In addition to the initial period, we define four consecutive 30-year periods: 1885–1914, 1915–1944, 1945–1974, and 1975–2004. Using the National Bibliography, we create an independent network for each period. For comparison with Lydia Koidula, we select several names from the previous graph and calculate the betweenness centralities for each period. Since the networks from different periods are not of the same size, we compare the relative, rather than absolute, centrality of the individuals.

Figure 6 shows the percentage of the most central nodes in which Koidula and her contemporaries belong at different times.

Who will remain famous?

As seen, Koidula emerged as one of the most central Estonian authors in the decades following her death in 1886, and she remained among the 0.2–6.5 percent of the most central authors until the early 21st century. This suggests that Koidula’s works continued to be published, edited, commented on, translated, and reprinted by many important figures in Estonian literary circles.

Jakobson's posthumous importance sharply declined during the period of independence but then rose again during the Soviet era – partly due to his willingness to cooperate with the Russian imperial authorities – although it never exceeded the 12 percent mark. Willigerode and Brandt's importance also declined, eventually fading completely, as neither of them were published for a significant period of time.

Koidula's continued popularity is certainly partially due to the specific nature of her genre, as poetry is more timeless compared to other genres. For example, Friedrich Brandt, also known as Priidik Prants, was one of the most prolific writers of the National Awakening era. Brandt authored nearly a hundred works and translated over twenty into Estonian. However, his writings—mainly hymnals, educational pamphlets etc — were likely more strongly tied to their time and no longer resonated as strongly with later generations.

At the same time, it must not be forgotten that Lydia Koidula’s freedom to act was strongly limited by her gender. In the 19th century, women had very few opportunities to participate in public life. Disseminating written works to the same extent as men would have been unthinkable, and this is reflected in her modest position in the National Awakening network.

The traces of women's activities are often more hidden, with works either published anonymously or under pseudonyms, or originating from private correspondence.4 However, it should be noted that while Koidula was ranked only 133rd in the entire network from 1855 to 1885 (meaning among both Estonian- and foreign-language authors, publishers, and other figures), and thus in the top 25 percent, there was no other woman more central than her during that period.

In conclusion, we can say that historical data and digital humanities methods help to understand complex social and cultural relationships in new ways. They also shed light on figures who played a crucial role in their time but have been forgotten, and in some cases, help balance the image of the past shaped by later layers. This case study has highlighted that the Estonian literary culture of the National Awakening involved close cooperation among authors, publishers, and artists working in various languages.

1. The national bibliography consolidates data on all printed works that have been published in Estonia, in the Estonian language, or by Estonians. The dataset used for this analysis is the section of the national bibliography that includes books, which can be freely downloaded here: https://zenodo.org/records/8228805. Before constructing the network, the data has been cleaned and enriched in various ways.

2. Lust, Kersti; Orasmaa, Siim; Maarja-Liisa Pilvik (2023). Kes kellega kohut käis? Vallakohtuprotokollide analüüs. Acta Historica Tallinnensia, 29 (1), 35−64. DOI: 10.3176/hist.2023.1.02.

3. The Python package NetworkX and the desktop application Gephi have been mainly used for the analyses and visualizations here.

4. In the case of Koidula, his long-standing pen-friendship with Kreutzwald can be clearly highlighted, which was recently republished in a fresh form. (Edited by Mart Lepik and Kanni Labi, Estonian Literary Museum 2023).

This post has been translated using ChatGPT.

National Library of Estonia

Tõnismägi 2, 10122 Tallinn

+372 630 7100

info@rara.ee

rara.ee/en